In this Article

Cervical Cancer

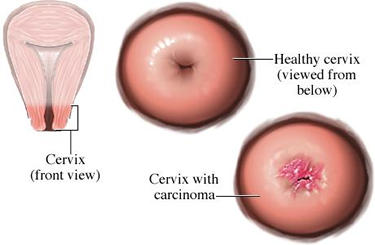

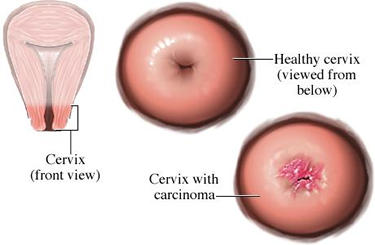

What Is Cervical Cancer?

Cervical cancer is a disease caused by the abnormal growth and division of cells that make up the cervix, which is the narrow, lower end of the uterus (womb).

“Cancer” is the name for a group of diseases in which certain cells in the body have changed in appearance and function. Instead of dividing and growing in a controlled and orderly way, these abnormal cells can grow out of control and form a mass or “tumor.”

A tumor is considered

The cervix is composed of three layers of tissue:

- An outer lining known as the serous membrane (slippery covering)

- A middle, muscular layer

- An inner lining known as the mucous membrane, which is composed of thin, flat, scaly cells called squamous cells. This inner lining has many tiny glands that secrete a clear, lubricating mucous.

Nearly all cervical cancers arise from the cells of the inner lining of the cervix.

Normally, cervical cells grow in an orderly fashion. However, when control of that growth is lost, cells divide too frequently and too fast.

Certain well-defined cellular changes may progress to cervical cancer:

- Mild cervical

dysplasia results when irregular cells are limited to the deepest one-third of the surface cell layer (known as theepithelium ) that lines the cervix. - Moderate cervical dysplasia occurs when uncontrolled cell growth continues, and up to two-thirds of the surface cell layer is abnormal.

- If abnormal cell growth progresses to include the full thickness of the surface cell layer, the condition is known as severe cervical dysplasia, or carcinoma in situ, or CIS. Carcinoma in situ does not penetrate surrounding tissues, stays within the confines of the epithelium, and is considered benign.

A tumor is considered malignant (cancerous) if abnormal cells:

- Penetrate the membrane that separates the surface cell layer and the underlying supportive tissue (called the stroma) of the cervix.

- Spread to the surrounding tissues or organs.

There are several types of cervical cancer:

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common type of cervical cancer, accounting for 85% to 90% of all cases. It develops from the cells that line the inner part of the cervix, called the squamous cells. It usually begins where the part of the cervix that connects with the

vagina (called the ectocervix) meets the part of the cervix that opens into the uterus (called the endocervix). - Adenocarcinoma develops from the column-shaped cells that line the mucous-producing glands of the cervix. In rare instances, adenocarcinoma originates in the supportive tissue around the cervix. Adenocarcinoma accounts for about 10% of all cervical cancers.

- Mixed carcinomas (for example, adenosquamous carcinomas) combine features of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.

|

Nice To Know: Q. Is cervical cancer curable? A. If caught in the early stages, cervical cancer is almost 100% curable. The chances of detecting cervical cancer at an early stage are greatly increased by having regular. Pap smears are probably the most successful of all screening procedures ever devised to detect early cancer. For more detailed information about pap smear, go to PAP smears. |

|

Facts About Cervical Cancer

|

Who Develops Cervical Cancer?

Cervical cancer is most often diagnosed in women who are between the ages of 50 and 55.

- Girls under age 15 rarely develop the disease, but the risk of cervical cancer does rise between the late teen years and the early 30’s.

- In both white and black women, cervical carcinoma in situ (a benign tumor) is most common between the ages of 25 and 30.

Some individuals are more likely to develop cervical cancer:

- City-dwellers and women who are members of racial or cultural minorities develop cervical cancer more often than other women do.

- Vietnamese women have the highest cervical cancer rate in the United States.

- Hispanics, Native Americans, and African Americans develop cervical cancer more often than white women do.

These statistics may reflect that:

- Many recent immigrants and other minority groups wrongly believe that a woman who isn’t sexually promiscuous doesn’t need to have a

Pap test . - African American women tend to have Pap tests less often than white women.

What Causes Cervical Cancer?

We don’t know exactly what causes cervical cancer, but certain risk factors are believed to have an effect. Medical history and lifestyle – especially sexual habits – play a role in a woman’s chances of developing cervical cancer.

The most significant risk factors are:

Various other risk factors have also been identified.

Human Papilloma Virus (HPV)

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a virus that can infect:

- The genital tract

- The external genitals

- The area around the anus

HPV has nothing to do with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. There are 46 genetic types of HPV, but not all are dangerous. Only certain types of HPV, which can be transmitted from one person to another during sexual contact, increase the risk of cell dysplasia (abnormal cell growth) and/or progression to cervical cancer.

The HPV types that produce genital warts (lesions that are raised and bumpy, or flat and almost impossible to see) are different from those that cause cervical cancer. However, women who have a history of genital warts have almost twice the risk of an abnormal Pap smear as other women.

|

Nice To Know: Hybrid Capture Test This new test, approved by the FDA in 1999, is able to detect 14 types of human papillomavirus (HPV) that can infect the |

Sexual History

A woman has a higher-than-average risk of developing cervical if she:

- Has had multiple sexual partners

- Began having sexual relations before the age of 18

- Has a partner who has had sexual contact with a woman with cervical cancer

Other Risk Factors

It is probable that other factors contribute to cervical cancer, such as:

- Poverty. Women who are poor may not have access to medical services that detect and treat

precancerous cervical conditions. When such women develop cervical cancer, the disease usually remains undiagnosed and untreated until it has spread to other parts of the body. Women who are poor are often undernourished, and poor nutrition can also increase cervical cancer risk. Pap test history. Not having regular Pap tests increases the chance of unrecognized cervical cancer. Between 60% and 80% of women with newly diagnosed cervical cancer have not had a Pap test in at least five years.- Tobacco use. Women who smoke are about twice as likely to develop cervical cancer as women who do not. The more a woman smokes – and the longer she has been smoking – the greater the risk.

- Eating habits. A diet that doesn’t include ample amounts of fruits and vegetables can increase a woman’s risk of developing cervical cancer.

- Weakened immune system. A woman whose immune system is weakened has a higher-than-average risk of developing cervical lesions that can become cancerous. This includes women who are HIV-positive (infected with the virus that causes AIDS). It also includes women who have received organ transplants and must take drugs to suppress the immune system so that the body won’t reject the new organ.

For more detailed information about AIDS, go to AIDS And Women.

- Hormonal medications. Some experts suggest that hormones in oral contraceptives (birth control pills) can make women more susceptible to Human papillomavirus (HPV). At least one study has indicated that taking birth control pills significantly increases a woman’s risk of developing HPV-related genital warts. Other research suggests that using oral contraceptives for five years or longer slightly elevates a woman’s risk of developing cervical cancer, especially if she began taking the Pill before the age of 25.

- Diethylstilberstrol (DES). A rare type of cervical cancer has been diagnosed in a small number of women whose mothers took diethylstilbestrol (DES), a medicine that was once used to prevent miscarriage.

- Douching. Because douching may destroy natural antiviral agents normally present in the

vagina , women who douche every week are more apt to develop cervical cancer than women who do not. - Chemical exposure. Women who work on farms or in the manufacturing industry may be exposed to chemicals that can increase their risk of cervical cancer.

Women with a weakened immune system due to the virus that causes AIDS are more likely to develop cervical cancer:

- Cervical cancer is very common in women who are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- Cervical cancer is sometimes the disease that first suggests a diagnosis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

- HIV can compound the effects of Human papillomavirus (HPV), causing cervical changes to progress more rapidly into cervical cancer than they otherwise might.

What are the Symptoms of Cervical Cancer?

Symptoms of cervical cancer don’t usually appear until the abnormal cells invade nearby tissue.

Symptoms can include:

- Abnormal bleeding

- Heavier, long-lasting periods

- Unusual vaginal discharge

- Pelvic pain

Abnormal bleeding may occur:

- Between menstrual periods

- After menopause

- After intercourse

- After a pelvic examination

These symptoms are not always a sign of cervical cancer. They can be caused by sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or other conditions. Your doctor can determine the cause of these symptoms.

|

Need To Know: Q. If I have no abnormal bleeding, does it mean I don’t have to worry about cervical cancer? A. Early cervical changes, and early cervical cancer, may cause no symptoms at all. Unfortunately, abnormal bleeding often doesn’t begin until the disease has become invasive, that is, until the abnormal cells have invaded nearby tissue. |

Can Cervical Cancer be Prevented?

Early-stage cervical cancer and precancerous cervical conditions are almost 100% curable.

The most common forms of cervical cancer begin with changes in cervical cells.

If these changes are detected early enough, treatment can be started immediately to prevent cervical cancer from developing.

The best way to detect early cervical cancer and precancerous conditions of the cervix is to have a gynecologic examination and Pap test.

|

Nice To Know: The American Cancer Society recommends that a woman have her first annual Pap test when she becomes sexually active or reaches the age of 18. |

Because cervical cancer usually progresses slowly, some physicians feel that a woman doesn’t need to have a Pap test every year if she:

- Is 65 years of age or older

- Has had normal Pap tests for three years in a row

Many experts recommend a Pap test every three years for women who have had a

|

Nice To Know: Women who have cervical cancer risk factors and who don’t have regular gynecologic examinations are increasingly likely to:

|

How Does Cervical Cancer Progress?

In many women, infection with certain types of human papillomavirus (HPV) is the first step in the progression from a normal cervix to cervical cancer. Recognized as the main cause of cervical cancer, sexually transmitted HPV induces the growth of abnormal cells that can become malignant.

Some experts feel that these changes are unlikely to progress to cancer in healthy women who don’t smoke or have other cervical cancer risk factors.

Precancerous Conditions

It usually takes many years for cancer of the cervix to develop, but the process also can take place in less than 12 months. As cancer cells form, cells of abnormal size and shape appear on the surface of the cervix and begin to multiply.

Cervical dysplasia is the term used to describe the early growth of abnormal cells on the cervix that could progress to cancer. Cervical dysplasia is usually the first stage of cervical cancer, but women who have cervical dysplasia do not always develop cervical cancer.

“Dysplastic” cells look like cancer cells, but they are not considered malignant because they remain on the surface of the cervix and have not invaded healthy tissue.

Precancerous conditions are classified in three ways:

- CIN I – This classification involves mild dysplasia, in which abnormal cells are limited to the outer one-third of the surface cell layer (

epithelium ) that lines the cervix. This classification includes cell changes caused by the human papillomavirus. It is common in young women and appears most often between the ages of 25 and 35. - CIN II – This classification involves moderate dysplasia, in which abnormal cells make up about one-half of the thickness of the surface layer (epithelium).

- CIN III – This classification involves severe dysplasia, in which the entire thickness of the epithelium is composed of abnormal cells, but these cells have not yet spread below the surface. This category is also called carcinoma in situ. Severe dysplasia is most common in women between the ages of 30 and 40.

Without treatment, severely dysplastic cells are likely to penetrate deeper layers of the cervix and spread to other organs and tissues. This process, which may not occur until months or years after the abnormal cells first appear, is called invasive cervical cancer.

Pap Test Classification

The results of Pap tests are often classified by a method known as the Bethesda system. According to this system, the Pap report will state:

- Whether the sample is good or not (describing samples as either satisfactory, suboptimal, or unsatisfactory)

- Whether the results are normal or abnormal

Abnormal results are divided into three categories:

- Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS)

- Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LGSIL)

- High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSIL)

1. ASCUS. This category describes Pap smears in which there are abnormal cells on the surface of the cervix.

2. LGSIL. This category is used to describe Pap smears that show mild dysplasia. In mild dysplasia, abnormal cells are limited to the deepest one-third of the epithelium (surface cell layer) that lines the cervix. Also known as CIN I, this category includes cell changes caused by human papillomavirus (HPV).

3. HGSIL. This category describes Pap smears that show either:

- Moderate dysplasia (also known as CIN II), with abnormal cells making up about one-half of the thickness of the surface lining

- Severe dysplasia (also known as carcinoma in situ or CIN III), in which the entire thickness of the epithelium is composed of abnormal cells, but such cells have not yet spread below the surface.

For Further information about pap tests, go to Pap Smear.

Staging of Cervical Cancer

“Staging” is a method that has been developed to describe the extent of cancer growth. The stage of cervical cancer describes the tumor’s:

- Size

- Depth of penetration within the cervix

- Spread within and beyond the cervix

Staging allows the physician to customize cancer treatment and to predict how a patient will fare over time. In general, the lower the stage, the better the person’s prognosis (expected outcome).

The physician uses all available findings to choose a stage that best describes the woman’s condition.

Cervical cancer is staged by information that is obtained through:

- Biopsy (removal of tissue for examination)

- Information gathered from the pathology report that accompanies a biopsy

- Cystoscopy (visual examination of the urinary tract with a camera-like instrument called an endoscope)

- Abdominal ultrasound (which uses high-frequency sound waves to produce an image of the inner body)

- Computed tomography (CT) scan (a computer-assisted technique that produces cross-sectional images of the body)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (or MRI, which uses powerful magnets to create finely detailed images of body tissue)

Staging With The Figo System

Cervical cancer staging is usually described in terms of the FIGO system, a staging scheme developed by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. The FIGO classifications are grouped within basic stages labeled stage 0 through stage IV (0-4):

- Stage 0 – Carcinoma in situ.

Tumor is present only in theepithelium (cells lining the cervix) and has not invaded deeper tissues. - Stage I – Invasive cancer with tumor strictly confined to the cervix.

- Stage IA – In this earliest form of stage I, a very small amount of tumor can be seen under a microscope.

- Stage IA1 – Tumor has penetrated an area less than 3 millimeters deep and less than 7 millimeters wide.

- Stage IA2 – Tumor has penetrated an area 3 to 5 millimeters deep and less than 7 millimeters wide.

- Stage IB – This stage includes tumors that can be seen without a microscope. It also includes tumors that cannot be seen without a microscope but that are more than 7 millimeters wide and have penetrated more than 5 millimeters of connective cervical tissue.

- Stage IB1 – Tumor that is no bigger than 4 centimeters.

- Stage IB2 – Tumor that is bigger than 4 centimeters. Tumor has spread to organs and tissues outside the cervix but is still limited to the pelvic area.

- Stage II – Invasive cancer with tumor extending beyond the cervix and/or the upper two-thirds of the

vagina , but not onto the pelvic wall.- Stage IIA – Tumor has spread beyond the cervix to the upper part of the vagina.

- Stage IIB – Tumor has spread to the tissue next to the cervix.

- Stage III – Invasive cancer with tumor spreading to the lower third of the vagina or onto the pelvic wall; tumor may be blocking the flow of urine from the kidneys to the bladder.

- Stage IIIA – Tumor has spread to the lower third of the vagina.

- Stage IIIB – Tumor has spread to the pelvic wall and/or blocks the flow of urine from the kidneys to the bladder.

- Stage IV – Invasive cancer with tumor spreading to other parts of the body. This is the most advanced stage of cervical cancer.

- Stage IVA – Tumor has spread to organs located near the cervix, such as the bladder or

rectum . - Stage IVB – Tumor has spread to parts of the body far from the cervix.

- Stage IVA – Tumor has spread to organs located near the cervix, such as the bladder or

The lower the stage number, the less the cancer has grown and spread. For example, a “stage I” cervical cancer is relatively small and has not yet spread beyond the pelvic area. By contrast, a “stage IV” cancer is much more serious, as it has already spread to the lymph nodes (the body’s drainage system) as well as to other locations.

How is Cervical Cancer Diagnosed?

Routine screening for cervical abnormalities can detect early-stage cancer and precancerous conditions that could progress to invasive disease. The process begins with a Pap test, also known as a Pap smear.

For further information about pap smear, go to Pap smear.

This painless office procedure detects about 95% of all cervical cancers and precancerous cervical conditions.

To perform a Pap test, a health professional uses a spatula, brush, or cotton swab to collect cells from the

If The Pap Test Suggests A Problem

If the Pap test results suggest a problem, the physician will then conduct additional tests. These may include:

- ThinPrep Pap test

- Speculoscopy

- Schiller test and colposcopy

- Colposcopy-directed biopsy

- Endocervical curettage

- Cone biopsy

- Dilation and curettage (D&C)

- Cervicography

The ThinPrep Pap Test, which has been approved by FDA and has been described as more effective than a conventional Pap smear, is a liquid-based test that employs a fluid medium to collect and preserve cervical cells. A woman who receives a ThinPrep Pap Test will not experience any difference in the procedure used to collect the sample of cervical cells.

Recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), this procedure involves the use of a magnifier and a special wavelength of light. Speculoscopy allows the physician to see cervical abnormalities that would otherwise be undetectable when performing a Pap test.

A physician performing the Schiller test applies a vinegar-like solution to the cervix and then coats it with iodine. Next, the physician performs a colposcopy, which is an examination of the cervix with a magnifying instrument called a colposcope.

Healthy cervical cells look brown, whereas abnormal cells appear white or yellow. The Schiller test and colposcopy are painless office procedures that have no side effects.

If colposcopy reveals abnormal areas on the cervix, the physician will order a biopsy – the removal of tissue for examination under a microscope by a cytopathologist (a specialist who studies cells in order to diagnose disease).

The physician uses forceps to remove small pieces of cervical tissue from areas of the cervix where abnormal-looking tissue has been detected. Local anesthetic is sometimes used to numb the cervix, and a woman who undergoes this office procedure may briefly experience pain, mild cramping, or light bleeding.

This procedure – which generally is performed at the same time as colposcopic biopsy – removes cells from the endocervix (part of the cervix that opens into the

- Local anesthetic may be used to numb the cervix before the physician proceeds.

- Next, a narrow instrument called a curette is inserted into the endocervix.

- Cells are then removed from this region, which cannot be seen during colposcopy.

A woman who has endocervical curettage may experience menstrual-type cramping or light bleeding for a short time afterward.

This procedure consists of removing a cone-shaped piece of tissue from the cervix. Tissue is removed from the area between the ectocervix (the part of the cervix that connects with the

The two methods commonly used to perform cone biopsy are:

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) – This procedure is conducted in a physician’s office under local anesthesia (the woman will be awake but pain will be blocked). A wire heated by electrical current is used to remove cervical tissue for laboratory analysis. The procedure takes about 10 minutes. Mild cramping may occur during the procedure and afterward. Mild or moderate bleeding may persist for several weeks.

- Cold knife cone biopsy – The physician uses a surgical scalpel or laser (intense, focused light beam) to remove abnormal cervical tissue. Cold knife cone biopsy is performed in a hospital under general anesthesia. A woman who undergoes the procedure can go home the same day but may experience cramping and bleeding for a few weeks afterward.

If a Pap test doesn’t clearly indicate whether abnormalities are caused by problems in the cervix or in the endometrium (lining of the uterus), the physician may conduct a dilation and curettage (D&C). During a “D&C,” the physician enlarges the cervix (dilation) and scrapes the inside of the uterus and cervical canal (curettage) to remove tissue for microscopic analysis.

This procedure may be performed in a doctor’s office without anesthesia or in an outpatient facility or hospital with epidural, spinal, or general anesthesia. When a D&C is performed without anesthesia, most women report cramps as the cervix is opened. After a D&C, some women experience complications such as bleeding, infection, or – in rare cases – perforation (piercing) of the uterus. D&C’s have been performed for many years and, in general, are very safe.

This diagnostic procedure enables a physician to obtain and examine a photographic image of the cervix. Cervicography may clarify abnormal Pap test results in women at above-average risk of developing cervical cancer. It could eventually reduce the need for colposcopy.

If The Cancer Has Spread

If the physician suspects that

- Cystoscopy

- Proctoscopy

- Computed tomography (Ct Scan)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- IVP

- Barium enema

- Chest x-ray

This procedure (also known as cystourethroscopy) lets the physician see the inside of the bladder, bladder neck, and urethra.

During cystoscopy, a cystoscope (thin, telescope-like tube with a tiny attached camera) is inserted into the bladder through the urethra (the passage through which urine passes from the bladder out of the body). This allows the physician to see whether cancer has spread from the cervix to the bladder or urethra.

Conducted under local or general anesthesia, cystoscopy can also be used to remove small tissue samples for microscopic examination.

During this procedure, the physician uses a proctoscope (a lighted tube), which is inserted into the rectum to examine the rectum or pelvis. In this way, the doctor can determine whether cancerous cells have spread to these organs from the cervix.

Computed tomography is an imaging technique in which an x-ray rotates around the body and takes pictures (“scans”) at many angles. A computer puts the scans together and creates detailed images of the body’s organs in cross-section.

Sometimes a special dye known as contrast medium is injected or drunk to highlight body parts during CT scanning. For example, contrast medium may be used to highlight the intestines and emphasize any spread of cervical cancer within the pelvic cavity and/or to the lymph nodes.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

An MRI is another computer-assisted imaging method. It uses a powerful electromagnet to activate the water molecules within the body and create finely detailed images of tissue. This technique is sometimes used to determine whether cancer has spread from the cervix to the lymph nodes or other nearby organs.

An intravenous pyelogram (IVP), also called intravenous urography, is a urinary system x-ray conducted to detect abnormalities in the urinary tract. Contrast dye is injected into a vein. Then the physician traces the route of the dye as it is removed from the kidneys and passed through the ureters (tubes that carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder) to the bladder.

This procedure may be used to identify urinary tract abnormalities caused by cancer that may have spread from the cervix.

This is a radiographic procedure in which contrast medium is introduced into the bowels through the anus so that the lower intestinal tract is visible on an x-ray.

This imaging procedure shows whether cancer has spread from the

How is Cervical Cancer Treated?

The main types of cervical cancer treatment are:

- Surgery, which may include a hysterectomy

- Radiation therapy

- Chemotherapy

Also used in cervical cancer treatment are biological therapy and other therapies such as clinical trials.

The type of treatment that is most appropriate for each case depends primarily on how early the cervical cancer is diagnosed. Other factors that affect treatment options are:

- Location of the tumor within the cervix

- Tumor type

- The woman’s age

- Her general health

- Her childbearing plans

- Whether or not the woman is pregnant

All treatments for invasive cervical cancer are associated with potentially serious side effects. In addition, women of childbearing age who have invasive cervical cancer must cope with the emotional consequences of premature menopause and infertility. Many people find strength in the support of counselors, clergy, medical personnel, and other women who share their fight and their fears.

In addition to standard treatments, women with cancer that has spread to distant organs/sites may decide to participate in clinical trials (experimental studies) that offer new medications or other therapies.

Surgery

Both surgery and radiation therapy are equally effective strategies for women who have early cervical cancer. Each form of treatment has a survival rate of 85% to 90%. The factors that influence the choice between radiation therapy and surgery include the woman’s age, health, and the extent of the disease.

The surgical procedures used to treat early cervical cancer include:

- Laser surgery. This outpatient treatment for cancer that has not spread uses a laser (a focused, high-energy light beam) to vaporize abnormal cells. Laser surgery can also be used to remove small pieces of tissue for laboratory analysis. It is not used to treat invasive cervical cancer.

- Cryosurgery. Cryosurgery kills abnormal cervical cells by freezing them with a metal probe cooled with liquid nitrogen. This procedure, which can be performed in a physician’s office, is used to treat cancer that has not penetrated deep layers of cervical tissue or spread beyond the cervix.

- Conization (cone biopsy). This procedure, which can be used for diagnosis as well as treatment, uses a surgical scalpel, laser knife (cold cone knife), or LEEP (LEETZ) procedure to remove a small amount of cone-shaped tissue from the cervix. Physicians usually use this procedure to establish a diagnosis of cervical cancer before performing surgery or initiating radiation therapy.

Conization rarely is used as the sole treatment for this disease unless a woman wants to preserve her ability to have children and the microscopic amount of cancer present hasn’t spread beyond her cervix.

- LEEP (LEETZ). This procedure removes abnormal tissue with a thin wire heated by electricity. It is used to treat cancer that has not spread beyond the area where it originated.

Laser surgery, cryosurgery, LEEP, and conization almost always remove or destroy all

Some individuals who undergo surgery may require additional radiation therapy or chemotherapy afterward. Women with very advanced cancers often require combinations of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

Although women with later-stage cervical cancers usually receive radiation therapy, some individuals select hysterectomy (surgical removal of the

- Preserve the ovaries and

vagina - Reduce treatment time

- Allow for a more thorough examination of cancerous lesions

Women who have had a hysterectomy cannot become pregnant.

There are several types of hysterectomy:

- Simple (total) hysterectomy is used to treat microscopic cancer that hasn’t spread beyond the uterus, and also some cases ofcarcinoma in situ. In simple hysterectomy:

- The uterus (including the cervix) is removed.

- The vagina remains intact.

- The ovaries (the two reproductive glands in which the eggs and the female sex hormones are made) and the fallopian tubes (which carry the eggs into the uterus) are also left intact. They are removed only if they are affected by some other disease.

- Pelvic lymph nodes, the parametrium (tissue surrounding the uterus), and the ligaments in the pelvis are not removed.

A simple hysterectomy can be performed in two ways:

- A vaginal hysterectomy involves removing the organs through the vagina.

- An abdominal hysterectomy involves removing the organs through an incision in the abdomen.

Although this operation usually doesn’t affect sexual desire or the ability to have intercourse, a woman who has had a total hysterectomy no longer menstruates (has periods) and can’t become pregnant. Yet, because the ovaries remain, she will not experience early menopause, which is the end of menstruation.

- Radical hysterectomy is performed once cancer has spread beyond the cervix. It involves the removal of the:

- Uterus

- Cervix

- Parametrium (tissue surrounding the uterus)

- Ovaries

- Fallopian tubes

- Upper vagina

- Some or all of the local lymph nodes

How-To Information:

What to expect with hysterectomy

- A woman who has had an abdominal hysterectomy can expect to spend three to five days in the hospital and should recover completely within four to six weeks.

- A woman who has had a vaginal hysterectomy can expect to spend one or two days in the hospital and make a complete recovery in two or three weeks.

- A woman who has had radical hysterectomy should expect to spend five to seven days in the hospital. She may experience difficulties controlling her bladder or moving her bowels normally. Medication or a catheter will help these problems. She can expect to resume normal activities – including sex – within four to eight weeks.

- Surgical complications are rare but can include excessive bleeding, infection at the site of the incision, and damage to the woman’s urinary or intestinal system.

Nice To Know:

After a woman’s uterus is removed, she no longer menstruates. If her ovaries are also removed, she’ll begin experiencing the symptoms of menopause. These symptoms are likely to be more intense than those experienced during the natural course of menopause.

Hormone replacement therapy, which involves taking the hormones estrogen and/or progesterone, can relieve these symptoms.

- Pelvic exenteration. This rare and extreme procedure is used to treat recurrent cervical cancer that has spread to surrounding organs. Pelvic exenteration removes the same organs and tissues as radical hysterectomy. In addition, though, pelvic exenteration may remove the bladder,

rectum , part of the colon, and/or vagina.If the bladder needs to be removed:

- Surgeons who must remove the bladder may connect a short segment of the intestine to the abdominal wall. This allows urine to periodically drain into a catheter (small tube) that is placed within a small opening in the abdomen. Or,

- The surgeon may attach a small plastic bag to the front of the abdomen to collect a continuous flow of urine.

If the rectum (end of the large intestine) needs to be removed, surgeons must create a new way for the woman to eliminate solid waste. This can be done by:

- Attaching the remaining intestine to the abdominal wall. This procedure, known as a colostomy, allows solid waste to pass through the opening in the abdomen into a small plastic bag at the front of the abdomen.

- Reconnecting the healthy sections of the colon. A woman who undergoes this procedure doesn’t have to wear a bag or other external appliance to collect waste.

If the vagina has to be removed, plastic surgery must be performed to create an artificial vagina. Surgeons will use skin, muscle and/or intestinal tissue grafts to accomplish this. Such vaginal reconstruction is a very rare procedure.

Radiation Therapy (Radiotherapy)

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays to destroy cancer cells. Cancers that extend beyond the cervix into the pelvis, lower vagina, and urinary tract typically receive radiation.

- Radiation therapy can be combined with surgery or chemotherapy to treat early cervical cancers and more invasive stages of the disease.

- Radiation also can be used to relieve symptoms caused by advanced cancer.

Physicians treat cervical cancer with external beam radiation, radioactive implants, or a combination of these therapies.

External beam radiation is administered the same way as a diagnostic x-ray. External beam radiation is usually given five times a week for five or six weeks, with an extra boost of radiation at the end of that time.

Women are encouraged to remain as active as possible during the course of this therapy, but they may experience side effects in the target area such as hair loss, dry or irritated skin, or permanent darkening of the skin. Therefore, women who undergo radiation therapy should: practice good personal hygiene, use lotions or creams only with a physician’s approval, wear loose clothing, and expose the target area to air whenever possible.

Implant radiation (brachytherapy) puts cancer-killing radiation as close to the tumor as possible, but spares the healthy tissue nearby. The radioactive material is either placed in a capsule and inserted into the cervix, or placed in thin needles that are inserted directly into the tumor.

The woman stays in the hospital for one to three days while the implants remain in place. Repeated several times over a period of one to two weeks, brachytherapy can cause the treated area to look and feel sunburned. Treated tissues regain their normal appearance within 6 to 12 months.

A woman should not have sex until a few weeks after completing radiation therapy. These treatments can cause numerous side effects that can be severe but usually disappear after treatment is completed. Side effects include:

- Fatigue

- Diarrhea

- Frequent or uncomfortable urination

- Vaginal dryness

- Itching

- Burning

Other complications of external beam radiation and brachytherapy include:

- Proctitis (inflammation of the rectum)

- Cystitis (inflammation of the bladder)

- Vaginal scarring

- Anemia and/or bruising

- Increased risk of infection

- Sexual difficulties

- Premature menopause

- Vesicovaginal fistula (development of an abnormal tunnel between the vagina and the bladder or rectum)

Medications and special techniques can help a woman successfully manage the side effects and complications of radiation therapy. Regular medical monitoring can help to prevent cancer recurrence.

For further information about radiation therapy, go to Radiation Therapy.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the treatment of choice for cervical cancer that has:

- Spread too far from its origin to be treated by surgery or radiation

- Recurred (come back) after surgery or radiation therapy

Chemotherapy also may be used to:

- Relieve pain associated with advanced cervical cancer

- Shrink cancer to an operable size before surgery is performed. This is called neoadjuvant chemotherapy. It can help prevent cervical cancer from spreading.

The Drugs Most Often Used

The cytotoxic (cancer-killing) drugs most often used to treat advanced or recurrent cervical cancer are cisplatin (Cisplatinum®, Platinol®), ifosfamide (Ifex®), and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). Taken by mouth or injected into a vein, these drugs enter the bloodstream and destroy cancer cells that have spread from the cervix to distant parts of the body.

Other drugs that have been used to treat cervical cancer includecarboplatin (Paraplatin®), methotrexate, bleomycin, mitomycin C (Mutamycin®), and vincristine (Oncovin®).

Paclitaxel (Taxol®), a drug used in breast cancer, is also being tested in clinical studies of cervical cancer.

Chemotherapy usually is administered at an outpatient facility, physician’s office, or in the patient’s home; but a woman who is in poor health may be hospitalized for treatment. Chemotherapy treatments alternate with recovery periods that allow a woman to rest and regain her strength before the next round of therapy begins.

Combination chemotherapy (a combination of two or more chemotherapy drugs) may be more effective than any single drug. When used in association with surgery or radiation, chemotherapy can help to prevent the spread or recurrence of cervical cancer. Recent clinical trials have shown that cisplatin combined with radiation therapy improves survival rates for women with advanced cervical cancer.

A woman undergoing chemotherapy may experience side effects such as:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Appetite changes

- Mouth sores

- Vaginal sores

- Hair loss (temporary)

- Fatigue

- Bruising and bleeding

- Susceptibility to infection

- Anemia

- Menstrual cycle changes

- Early menopause

- Infertility

Side effects generally subside after treatment is completed. Most women who undergo chemotherapy for cervical cancer are already infertile as a result of surgery or radiation therapy. Physicians may prescribe hormones to help with symptoms of premature menopause.

Biological Therapy

Biological therapy can be used to treat cancer that has spread from the cervix to other parts of the body. Interferon – a cell protein that provides immunity to viral infections – is the type of biological therapy most often used. Biological therapy is usually administered on an outpatient basis and is sometimes combined with chemotherapy.

“Flu-like” side effects, among other complaints, have been reported by women who undergo biological therapy. These include:

- Fever and/or chills

- Muscle aches

- Weakness

- Diarrhea

- Rash

- Appetite loss

- Nausea or vomiting

- Easy bleeding or bruising

Side effects can be severe, but they generally subside after treatment is completed.

Other Therapies

A woman whose cancer is advanced and whose chance of survival is poor may choose to:

- Combine standard therapies with experimental treatment

- Enroll in a clinical trial designed to measure the effectiveness of new treatments for cervical cancer

Cervical Cancer and Pregnancy

Pregnant women generally do not develop cervical cancer. A woman who does, and whose disease is diagnosed at a very early stage, can safely continue her pregnancy. However, physicians usually recommend either:

- A cesarean section (delivery of the baby through an incision in the abdominal wall) followed by hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus) for delivery and treatment, or

- A vaginal delivery with hysterectomy several weeks later.

If a pregnant woman has advanced cervical cancer, she and her partner, together with the physician, must decide whether to continue or terminate the pregnancy.

A woman who decides to terminate the pregnancy usually undergoes a hysterectomy and/or radiation therapy. If the woman decides to continue the pregnancy, the baby should be delivered by cesarean section as soon as it is able to survive outside the womb.

Immediate treatment is the safest option for a pregnant woman with advanced cervical cancer.

What If Cervical Cancer Comes Back?

The recurrence (return) of cervical cancer can be

- Localized – confined to the pelvic organs near the cervix, or

- Metastatic – widespread throughout the bloodstream or lymphatic system to distant organs like the lungs, or bone

Pelvic exenteration is a treatment option for recurrent cervical cancer that is limited to the pelvic area. This rare procedure involves the removal of the uterus, related lymph nodes and tissues, and, possibly, the bladder, rectum, part of the colon, and/or vagina. Recurrent cancer cannot be eliminated in about 60% of affected women. In such cases, palliative (pain-relieving) radiation therapy or chemotherapy may reduce symptoms.

Chemotherapy and radiation are also used to relieve symptoms associated with cervical cancer that has spread to distant organs. These treatments can provide temporary relief in 15% to 25% of women with this disease.

Some women with cervical cancer that has spread may choose to enroll in clinical trials designed to evaluate

Living With Cervical Cancer

Even when cervical cancer is not life-threatening, the consequences of the disease can be life-changing. Women with cervical cancer are confronted with potentially overwhelming physical and emotional changes. It is beneficial to have:

- An understanding partner

- A supportive network of family and friends

- Additional valuable support from healthcare personnel, counselors, clergy, and other cervical cancer survivors

After treatment with surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy, the woman’s oncologist (cancer specialist) will provide a detailed schedule of follow-up visits. These visits may include further evaluation with:

- Imaging studies such as x-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Biopsies (removal of tissue for examination)

- Blood tests

Follow-up testing helps to determine whether the woman remains cancer-free or needs additional treatment.

Healthy living habits also can speed the recovery process and reduce the likelihood that cancer will recur. For example, a woman who has had cervical cancer should:

- Not smoke

- Avoid excessive alcohol use

- Exercise as soon and as much as permissible

- Choose a diet that includes low-fat, high-fiber foods like fruits, vegetables, and whole grains (Physicians may recommend a low- fiber diet for women who experience diarrhea or cramping as a result of radiation therapy)

What is the Outlook for Cervical Cancer?

On the horizon are activities that spell good news in the fight against cervical cancer:

- Improving the Pap test

- Developments in human papillomavirus (HPV) research

- Clinical trials and other research

Improving the Pap test

Engineers, scientists, and physicians are working together to improve the way cervical cell samples are collected and analyzed during a Pap test. Other researchers are evaluating new ways to manage women with mildly abnormal Pap tests. The results of this research will help women and their physicians to decide what to do when a Pap test appears to be abnormal.

|

Nice To Know: The number of new cervical cancer diagnoses and the number of cervical cancer deaths decline each year. Experts believe these statistics would decline even more rapidly if regular Pap tests were given to all women who are or have been sexually active or have reached the age of 18. |

Developments In Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) Research

Researchers are now developing simple and inexpensive laboratory tests that are capable of detecting cancer-causing strains of human papillomavirus (HPV). Such tests eventually will be available for widespread, routine use. In addition, researchers are in the process of creating vaccines that will:

- Destroy HPV before the virus is firmly established

- Produce an immune system response that kills or stops the growth of cancer cells that have spread beyond the

cervix

Improvements are also being made in HPV screening tests, which will identify women with HPV-related and cancer-related changes in cervical cells.

Clinical Trials And Other Research

Clinical trials – studies that evaluate the effectiveness of new drugs and other treatments in a controlled, clinical setting – are now underway in select groups of patients. These cervical cancer trials should help to determine the value of the latest anti-cancer therapies, such as:

- New chemotherapy medications

- Radiation techniques

- Combination therapies (for example, surgery plus radiation or chemotherapy)

In addition, cancer researchers are now studying the ways that oncogenes (genes that contribute to cancer) and

Frequently Asked Questions: Cervical Cancer

Here are some frequently asked questions related to cervical cancer.

Q: What causes cervical cancer?

A: We don’t always know what causes cervical cancer, just like we don’t know what causes most cancers. Not uncommonly however, this disease occurs when a virus or other factor causes cells within the

Q: Why do some women develop cervical cancer?

A: The primary risk factors associated with cervical cancer are age, a woman’s sexual habits, and infection with a high-risk strain of human papillomavirus (HPV). Lifestyle, race, and other factors probably affect a woman’s chances of developing cervical cancer.

Q: Can cervical cancer be prevented?

A: Routine Pap tests can detect almost all instances of early cervical cancer and

Q: How is cervical cancer diagnosed?

A: Routine screening for cervical abnormalities can detect early-stage cancer and precancerous conditions (that are not yet malignant).

Q: Why are regular Pap tests so important?

A: Cervical cancer grows slowly, and regular Pap tests can detect the disease in its earliest, most curable stages.

Q: Who should be screened for cervical cancer?

A: Every woman who has reached the age of 18 or who is or has been sexually active should have regular Pap tests.

Q: Is cervical cancer curable?

A: If caught in the early stages, cervical cancer is almost 100% curable. The chances of detecting cervical cancer at an early stage are greatly increased by having regular Pap smears. Pap smears are probably the most successful of all screening procedures ever devised to detect early cancer.

Q: How is cervical cancer treated?

A: The standard treatments for cervical cancer are surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

Q: What is the emotional impact of cervical cancer?

A: Because cervical cancer treatment often leaves a woman infertile, this disease can be especially devastating for women of childbearing age. Friends, family members, and professional caregivers can provide valuable emotional support.

Putting It All Together: Cervical Cancer

Here is a summary of the important facts and information related to cervical cancer.

- Cervical cancer – cancer of the

cervix , which is the lower part of theuterus – can be prevented. - Early-stage cervical cancer is almost 100% curable.

- Every woman who has reached the age of 18 or who is or has been sexually active should have regular Pap tests.

- Women who don’t have regular Pap tests are much more apt to develop cervical cancer than women who do.

- A woman’s sexual habits and

Pap test history are the best indicators of her chances of developing cervical cancer. - It is a myth that a woman only needs a Pap test if she is sexually permissive. Every woman over age 18 should get regular Pap tests.

- Early-stage cervical cancer causes no symptoms. Abnormal bleeding and other symptoms rarely occur before the disease has become invasive.

Glossary: Cervical Cancer

Here are definitions of medical terms related to cervical cancer.

Benign: Not cancerous.

Carcinoma in situ (CIS): A non-cancerous tumor that remains ‘in the site’ of origin and shows signs of becoming cancerous.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: Growth of abnormal cells on the surface of the cervix.

Cervix: The narrow, lower end of the uterus (womb).

Dysplasia: Potentially precancerous abnormality of cervical cells.

Epithelium: The covering of the internal and the external organs of the body, as well as the lining of vessels, glands, and organs. It consists of cells bound together by connective material, and it varies in the number of layers and the kinds of cells it contains.

Genital warts: Lesions produced by the human papillomavirus (HPV) and transmitted through sexual contact. The lesions may be raised and bumpy, or flat and almost impossible to see.

Human papillomavirus (HPV): Virus that is transmitted from one person to another during sexual contact, and that is considered to be the leading cause of cervical cancer. It has nothing to do with HIV (the virus that causes AIDS).

Hysterectomy: Surgical removal of the uterus.

Malignant: Cancerous.

Pap test: The Papanicolau test; a test that detects abnormalities in the cells of the female genital tract. The test is performed by a health care provider, who uses a small brush or swab to brush along the cervix in order to obtain a sample of cells, which are then studied under a microscope.

Precancerous: Having the potential to become malignant (cancerous).

Rectum: Section of the colon where solid waste is stored before passing out of the body.

Squamous intraepithelial lesion: Abnormal growth of flat, scaly cells on the surface of the cervix.

Systemic: Affecting the whole body.

Tumor: An abnormal mass of tissue that results from excessive cell division. A tumor may be benign (not cancerous) or malignant (cancerous).

Uterus: The female reproductive organ in which a fetus grows during pregnancy. Also called the womb.

Vagina: The passage that connects the female reproductive organs to the outside.

Additional Sources Of Information: Cervical Cancer

Here are some reliable sources that can provide more information on cervical cancer.

American Cancer Society (ACS)

Phone: (800) ACS-2345 (toll-free hotline)

www.cancer.org

National Cancer Institute (NCI), Cancer Information Service

9000 Rockville Pike

Phone: (800) 4-CANCER

Phone: 800-422-6237

www.nci.nih.gov

American Medical Women’s Association:

http://www.cancerlinks.org/cervical.html

American Social Health Association:

Phone: 877-HPV-5868 (HPV Hotline)

Cancer News on the Net:

http://www.cancernews.com/

Cervical Cancer List

Email: LISTSERVE@INFO.PATH.ORG To subscribe

National Cervical Cancer Coalition:

Phone: 800-685-5531

http://www.nccc-online.org

Women’s Cancer Network:

Phone: 888-444-4441

http://www.wcn.org