In this Article

ACL Tears

What Is The ACL (Anterior Cruciate Ligament)?

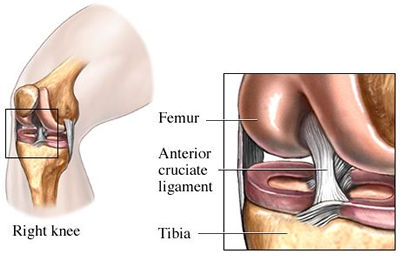

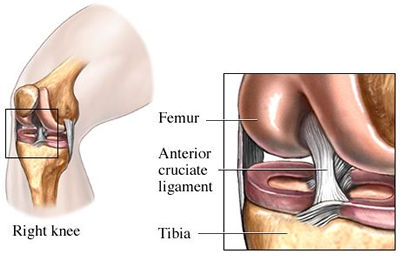

The ACL is short for Anterior Cruciate Ligament. It is one of 2 strong ligaments inside knee joint. The other is the PCL (posterior cruciate ligament). Cruciate means ‘crossing’. The 2 ligaments inside the knee joint ‘cross’ each other. Ligaments are strong, dense structures made of connective tissue that stabilize a joint. They connect bone to bone across the joint.

The ACL is often injured.

The function of the ACL is to provide stability to the knee and minimize stress across the knee joint:

- It restrains excessive forward movement of the lower leg bone (the tibia) in relation to the thigh bone (the femur).

- It limits rotational movements of the knee.

A tear of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) results from overstretching of this ligament when certain movements of the knee put too great a strain on the ACL

Its usually due to a sudden stop and twisting motion of the knee, or a force or “blow” to the front of the knee

The movements of the knee that can result in a tear of the ACL are described as follows:

- Hyperextension of the knee, that is, if the knee is straightened more than 10 degrees beyond its normal fully straightened position, is a very common cause of an torn ACL. This position of the knee forces the lower leg excessively forward in relation to the upper leg.

- Pivoting injuries of the knee with excessive inward turning of the lower leg can also damage the ACL.

Basically any athletic or non-athletic related activity in which the knee is forced into hyperextension and/or internal rotation may result in an ACL tear.

Often those are non-contact activities with the mechanism of injury usually involving:

- Planting and cutting – the foot is positioned firmly on the ground followed by the leg (and body for that matter) turning one direction or the other. Example: Football or baseball player making a fast cut and changing direction.

- Straight-knee landing – results when the foot strikes the ground with the knee straight.Example: Basketball player coming down after a jump shot or the gymnast landing on a dismount.

- One-step-stop landing with the knee hyperextended – results when the leg abruptly stops while in an over-straightened position.Example: Baseball player sliding into a base with the knee hyperextended with additional force upon hyperextension.

- Pivoting and sudden deceleration resulting from a combination of rapid slowing down and a plant and twist of the foot placing extreme rotation at the knee. Example: Football or soccer player quickly slowing down followed by a quick turn in direction.

The severity of the injury to the knee will depend on:

- The position of the knee at the time of the injury

- The direction of the blow

- The force of the blow

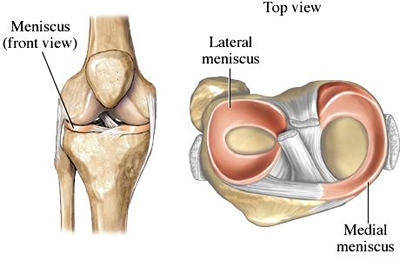

At least half of all ACL tears are associated with other soft tissue injuries in the knee, usually the medial meniscus or medial collateral ligament (see further below about the anatomy of the knee). When the ACL, medial meniscus and medial ligament are all torn the triad (3 injuries) is known as O’Donohugh’s triad.

About 40% of people who who tear the ACL describe a “popping sensation” at the time of injury (which may be the tear of the ACL or of the medical meniscus). The knee usually swells and is painful.

The tear of the ACL can be a partial tear or a complete tear.

Instability or a sensation the knee is “giving out” may be a major complaint following this injury.

Often, but not always, depending on a person’s activity level, a torn ACL needs to be fixed.

Unfortunately a simple repair by suturing the torn ligament together again is not effective. A successful repair involves completely replacing the torn ligament. There are a number ways that this can be done.

To read more about surgery needed for ACL tears and what’s involved please go to Surgery for ACL tears

Sports that cause ACL tears:

Hyperextension (forceful over-straightening of the knee) is most often caused by accidents associated with:

- Skiing

- Volleyball

- Basketball

- Soccer

- Football

Because the ACL becomes taut with inward rotation of the tibia, activities placing any excessive inward rotation of the tibia (turning the lower leg inward – usually seen from a plant and twist mechanism) are seen in sports such as:

- Football

- Tennis

- Basketball

- Soccer

Injury to the ACL may occur in other sports such as:

- Wrestling

- Gymnastics

- Martial arts

- Running

Non-Athletic-Related Injuries

Non-sport related injuries to the ACL result from similar contact and non-contact stresses on the ligament. Examples vary from being struck on the outer side of the knee to landing on the knee forcing it into an over-straightened position with the knee turned inward.

Motor vehicle accidents in which the knee is forced under the dashboard may also cause rupture of the ACL.

Repeated trauma and wear and tear can be a knee problem at any age causing small tears in the ligament, which over time become complete tears.

Facts about ACL tears:

- The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) provides almost 80% of the stability to the knee joint (counteracting forward movement of the tibia on the femur)

- More than 11.2 million visits are made to physicians’ offices because of a knee problem. It is the most often treated anatomical site by orthopedic surgeons.

- Of the four major ligaments in the knee, the anterior cruciate ligament and the medial collateral ligament are most often injured in sports.

- Reconstruction of a torn ACL is now a common procedure, with over 50,000 hospital admissions per year.

- ACL ruptures occur at a rate of 60 per 100,000 people per year. With society’s increasing interest in physical fitness, primary care physicians are seeing more athletic injuries. Along with these injuries are the commonly experienced ACL ruptures in athletes and non-athletes alike. Today’s athletes have greater than a 90% chance of returning to their pre-injury level of sports participation.

- ACL reconstruction is a highly successful operation. With good rehabilitation, 90% to 95% of individuals who undergo this surgery can expect to return to full sports participation within six months.

Diagnosing an ACL tear:

The diagnosis of an ACL tear is based on

- The doctor’s examination, as well as special tests which may include:

- Radiographic Evaluation

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

Physical Examination

The doctor will take a thorough history addressing how the injury occurred and ascertaining when the pain may have first appeared. Questions regarding any earlier knee injuries are important as often ligaments and cartilage structures may have been previously damaged. Any previous episodes of knee instability or the knee giving way, or previous injury to the knee, is important information.

The doctor can determine whether the knee is stable on examination. One simple but important test is called the Lachmans test. With the knee bent to 30 degrees, the doctor gently pulls on the tibia to check the forward motion of the lower leg in relation to the upper leg. A normal knee will have less than 2 to 4 mm of forward movement, with a firm stopping felt when no further movement is observed. In contrast, a knee with an ACL tear will have increased forward motion and a soft end feel at the end of the movement. This is because of the loss of the normal restraint of the forward movement of the tibia due to the torn ACL.

A similar test, with the knee bent to 90 degrees, is called the anterior drawer test. A more complex test is called the pivot shift test, in which greater stresses are put on the knee as it is straightened by the doctor from a bent and inwardly rotated position. If the knee “gives,” this is an indication that other stabilizing structures inside the knee must be torn besides the ACL. This test can sometimes only be done when the knee is completely relaxed. Because of this it may best be observed under anesthesia during the surgical procedure.

Radiographic Evaluation

Acute knee injuries generally warrant x-ray films. An x-ray cannot show an ACL tear because it is a soft tissue injury (and x-rays show the bones). But it can show an ACL injury if it is an ‘avulsion’, when the tendon has been pulled away with a bone fragment. An x-ray is also useful to exclude a possible concurrent bone injury, or see whether a pre-existing problem of the knee is present (for example, arthritis, or a previous bone injury, or loose bone fragments inside the joint).

MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging is a noninvasive test that produces an excellent image of all parts of the knee. It is the key investigation to determine whether an ACL tear is present. In this test, the individual lies in a hollow cylinder while powerful magnets create signals from inside the knee. These signals are then converted into a computer image that clearly shows any damage to the structures inside the joint. The images are valuable not only to determine the presence of an ACL tear, but also the degree of the tear along with any damage to related structures, such as a tear of the medial or lateral meniscus or of the collateral ligaments.

For further information about mri, go to MRI.

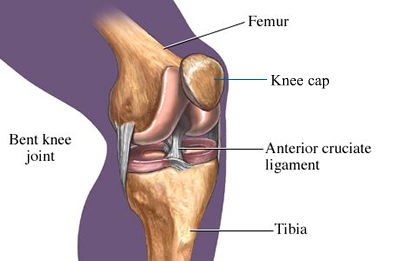

The knee is a hinge joint made up of three bones held firmly together by ligaments that stabilize the joint. The bones that meet at the knee are the upper leg bone (the femur), the lower leg bone (the tibia), and the knee cap (the patella). A smooth protective layer called cartilage, which allows the bones to glide smoothly upon each other, lines the bones inside the joint. In arthritis, this smooth lining becomes damaged.

Ligaments

Ligaments are dense structures of connective tissue that fasten bone to bone and stabilize the knee. Inside the knee joint are two major ligaments:

- The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)

- The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)

These cross in the center of the knee (that’s why they’re called cruciate ligaments -a crucifix is a cross). They control the backward and forward motion of the knee. The ACL in particular restrains excessive forward motion of the knee as well as the inward twisting or rotation of the knee. The ACL is frequently injured in severe twisting injuries of the knee.

Two other major ligaments are actually located outside the knee joint, on the outer and inner side of the knee. They act to stabilize the knee’s sideways motion. The ligament on the inner side of the knee is called the medial collateral ligament (MCL) (medial means inner side). The ligament on the outer side of the knee is the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) (lateral means outer side).

The patellar tendon (the ‘ligament’ of the knee cap) connects the lower part of the kneecap (patella) to the upper part of the tibia![]() , specifically to the lump one can feel just below the knee on the lower leg bone (the tibia). Part of this tendon is commonly used in reconstructing a torn ACL.

, specifically to the lump one can feel just below the knee on the lower leg bone (the tibia). Part of this tendon is commonly used in reconstructing a torn ACL.

Meniscus

The meniscus is a half-moon-shaped structure placed between the weight-bearing bone ends in the knee. There are two menisci in each knee, one on the inner side called the “medial meniscus” and one on the outer side called the “lateral meniscus.”

- The two menisci act as shock absorbers within the knee and also help spread the weight load.

- The meniscus is a type of cartilage, though it is different than the cartilage that lines the bones.

- The menisci may be torn during twisting movements of the knee. A meniscus is frequently torn at the same time an ACL tears during injury.

Muscles

Muscles control the movement of the knee joint. Rehabilitation of these muscles is most important following an ACL injury or reconstruction.

The major muscles of the knee joint involved with bending and straightening the knee are:

- Quadriceps

- Hamstrings

The quadriceps muscle is made up of the four large muscles at the front of the thigh (these muscles are the rectus femoris, the vastus lateralis, the vastus intermedius, and the vastus medialis). Together they form a large fleshy mass covering the front and sides of the thigh bone. This is the main muscle group that straightens the knee (called extension of the knee).

The hamstring muscles are the muscles at the back of the upper leg. They flex (bend backward) the lower leg. Individually, the muscles of the hamstrings are the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus.

The biceps femoris is a large muscle comprised of two heads called the long head and short head, converging to a single tendon as it inserts below the knee joint. This common tendon is located on the outer back corner of the knee and forms the outer hamstring. Another member of the hamstring muscles is the semitendinosus muscle originating from the back of the pelvis and crossing below the back of the knee joint. This muscle, along with the tendon from another hamstring muscle called the semimembranosus and yet another inner groin muscle called the gracilis muscle, form the inner hamstring.

Tendons are tough tissues that connect the muscles to the bone. The hamstring tendons are frequently used in reconstruction of the ACL.

What Causes An ACL Tear?

The ACL may tear when certain movements of the knee place a great strain on the ACL. These movements are:

- Hyperextension of the knee, that is, if the knee is straightened more than 10 degrees beyond its normal fully straightened position, is a very common cause of an torn ACL. This position of the knee forces the lower leg excessively forward in relation to the upper leg.

- Pivoting injuries of the knee with excessive inward turning of the lower leg can also damage the ACL.

Basically any athletic or non-athletic related activity in which the knee is forced into hyperextension and/or internal rotation may result in an ACL tear.

Activities placing the knee into hyperextension and /or the tibia into excessive inward rotation can be from either an outside force or non-contact in nature.

The severity of the injury to the knee will depend on:

- The position of the knee at the time of the injury

- The direction of the blow

- The force of the blow

Most ACL injuries occur during athletic activity. Often those are non-contact activities with the mechanism of injury usually involving:

- Planting and cutting – the foot is positioned firmly on the ground followed by the leg (and body for that matter) turning one direction or the other. Example: Football or baseball player making a fast cut and changing direction.

- Straight-knee landing – results when the foot strikes the ground with the knee straight. Example: Basketball player coming down after a jump shot or the gymnast landing on a dismount.

- One-step-stop landing with the knee hyperextended – results when the leg abruptly stops while in an over-straightened position.Example: Baseball player sliding into a base with the knee hyperextended with additional force upon hyperextension.

- Pivoting and sudden deceleration resulting from a combination of rapid slowing down and a plant and twist of the foot placing extreme rotation at the knee. Example: Football or soccer player quickly slowing down followed by a quick turn in direction.

About 40% of all individuals experience a “popping” sensation at the time of the injury, which is actually the tearing of the ligament tissue. At least half of all anterior ligament tears also cause injury to one of the menisci of the joint, which may also produce a tearing sensation.

Hyperextension (forceful over-straightening) is most often caused by accidents associated with:

- Skiing

- Volleyball

- Basketball

- Soccer

- Football

Because the ACL becomes taut with inward rotation of the tibia, activities placing any excessive inward rotation of the tibia (usually seen from a plant and twist mechanism) are seen in sports such as:

- Football

- Tennis

- Basketball

- Soccer

Injury to the ACL may occur in other sports such as:

- Wrestling

- Gymnastics

- Martial arts

- Running

Non-Athletic-Related Injuries

Non-sport related injuries to the ACL result from similar contact and non-contact stresses on the ligament. Examples vary from being struck on the outer side of the knee to landing on the knee forcing it into an over-straightened position with the knee turned inward.

Motor vehicle accidents in which the knee is forced under the dashboard may also cause rupture of the ACL.

Repeated trauma and wear and tear can be a knee problem at any age causing small tears in the ligament, which over time become complete tears.

Nice to Know:

Male/female comparisons

- Studies from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) have shown that female athletes injure the ACL more frequently than their male counterparts.

- The NCAA data also reports that female basketball and soccer players have a significantly higher incidence of knee injuries in general, and ACL injuries in particular, than their male counterparts.

- This greater incidence of ACL injuries in women probably originates from several interrelated factors such as hamstring-quadriceps strength imbalances, joint laxity, and the use of ankle braces.

Diagnosing An ACL Tear

The diagnosis of an ACL tear is based on

- The doctor’s examination, as well as special tests which may include:

- Radiographic Evaluation

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

Physical Examination

The doctor will take a thorough history addressing how the injury occurred and ascertaining when the pain may have first appeared. Questions regarding any earlier knee injuries are important as often ligaments and cartilage structures may have been previously damaged. Any previous episodes of knee instability or the knee giving way, or previous injury to the knee, is important information.

The doctor can determine whether the knee is stable on examination. One simple but important test is called the Lachmans test. With the knee bent to 30 degrees, the doctor gently pulls on the

A similar test, with the knee bent to 90 degrees, is called the anterior drawer test. A more complex test is called the pivot shift test, in which greater stresses are put on the knee as it is straightened by the doctor from a bent and inwardly rotated position. If the knee “gives,” this is an indication that other stabilizing structures inside the knee must be torn besides the ACL. This test can sometimes only be done when the knee is completely relaxed. Because of this it may best be observed under anesthesia during the surgical procedure.

Radiographic Evaluation

Acute knee injuries generally warrant x-ray films. An x-ray cannot show an ACL tear because it is a soft tissue injury (and x-rays show the bones). But it can show an ACL injury if it is an ‘avulsion’, when the tendon has been pulled away with a bone fragment. An x-ray is also useful to exclude a possible concurrent bone injury, or see whether a pre-existing problem of the knee is present (for example, arthritis, or a previous bone injury, or loose bone fragments inside the joint).

MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging is a noninvasive test that produces an excellent image of all parts of the knee. It is the key investigation to determine whether an ACL tear is present. In this test, the individual lies in a hollow cylinder while powerful magnets create signals from inside the knee. These signals are then converted into a computer image that clearly shows any damage to the structures inside the joint. The images are valuable not only to determine the presence of an ACL tear, but also the degree of the tear along with any damage to related structures, such as a tear of the medial or lateral

For further information about mri, go to MRI.

What Can Be Done For An ACL Tear?

The initial goals of treatment immediately after injury are to reduce pain and swelling and regain range of motion and strength. Even if surgery is likely, achieving as much knee motion and strength as possible can greatly reduce complications after surgery.

Immediately after the injury

Post injury exercises

Bracing

Immediately After The injury

Immediately after an ACL injury, the so-called R.I.C.E. treatment is recommended.

R.I.C.E. stands for:

- Rest – The individual is advised to rest the knee from weight-bearing activities allowing the swelling to settle.

- Ice – Placing a cold compress or ice pack on the knee is helpful in controlling inflammation as well as helping to reduce pain.

- Compression – Utilizing an ace wrap for compression around the knee is beneficial to control the swelling.

- Elevation – Lying down with the leg elevated higher than the level of the chest is helpful in controlling and reducing swelling.

The physician may request very gradual weight-bearing exercise immediately after the initial ACL injury. Braces used early after the injury are called rehabilitation kneebraces and are off-the-shelf designs used for conservative treatment of the ligament tear. This type of brace is also used for postoperative care of the injured ACL. The rehabilitation brace, also called a post-operative brace, is used immediately post-injury in an effort to put the joint at rest and help protect it, while still allowing appropriate but limited motion. This form of bracing is available in two particular types:

- Straight immobilizer – Made of foam with two metal rods down the side that is secured with Velcro and prevents all motion.

- Hinged brace – Allows range of motion to be set by tightening a screw control.

Post-Injury Exercises

As the swelling in and around the joint decreases and weight-bearing progresses, mild strengthening exercises are started.

Quadriceps sets are one example of strengthening exercises at this stage. With the knee placed at approximately 10 degrees from being straight, along with a small towel roll directly behind the knee, the individual pushes downward into the towel roll for a count of six to 10 seconds. This is repeated 10 times. It should be done several times throughout the day.

Increasing the range of motion of the knee becomes a very important part of the program to avoid joint stiffness and muscle tightness. Sliding the heel of the injured leg towards the buttock until a gentle stretch is felt is also a good exercise. This stretch is held for 10 to 20 seconds and is repeated 10 times, several times a day.

Bracing

Bracing for the anterior cruciate ligament comes in two forms:

- Rehabilitation Brace (described above)

- Functional Brace

Functional or sport braces are available both off-the-shelf and as custom-fit. Physicians prescribe this type of brace to treat the unstable knee in people when surgery is not recommended, as well as to protect the knee in those who have had surgery. Functional braces can be worn as the individual returns to work, training, or competition. But they may be most beneficial for individuals who have some instability and who place low to moderate stress loads upon the knee. It is important to the individual who does have instability of the knee from an ACL tear that functional knee braces will guarantee against instability in activities that require cutting, pivoting, or other quick changes in direction. A well-fitting brace will not restrict normal knee movement.

Do I need surgery for an ACL tear?

Treatment decisions for ACL tears are always individualized – tailored to each individual. The decision whether to offer surgery is based on the person’s age, activity level, how unstable the knee is, and whether other structures in the knee have been injured.

It is important to keep in mind that surgery to reconstruct a torn ACL is not an emergency for most people. Many people with a torn ACL do not need surgery at all. Even though the chances for complete success from surgery are now excellent, surgery is not for everyone. This is because not everyone needs the ligament repaired to return to his or her pre-injury level of function. It is important to distinguish whether the work, recreational, and athletic activities of the person is light, moderate, or strenuous. Another important issue that needs to be understood by the individual considering ACL reconstruction is that it requires many weeks and months of hard work in rehabilitation following the reconstruction. This needs commitment and time.

The Ultimate Deciding Factors…

- Whether the injury is a recent tear or an old ACL problem, individuals need to consider their present activity level and decide if their daily activities and livelihood would be affected by the injury. The question of whether to have surgery to reconstruct the torn ACL arises most frequently with less athletically inclined older persons. Generally in such people, if the instability is severe, and the knee is constantly buckling, the decision to offer surgery is intended to prevent further damage to the knee and stop the daily discomfort of the knee giving way.

- On the other hand, if the knee instability can be controlled by avoiding activities that the individual doesn’t really mind avoiding, then going the “conservative” route and avoiding surgery is often a very good choice – and many people are satisfied with it. Certainly, there are many older athletes who are willing to avoid basketball, soccer, or racquetball, and stick to jogging or biking for fitness. As long as their knees are stable and pain-free for these activities, they are happy. Also with the use of a functional brace, many of these people find they can do most of what they wish to do without significant problems.

- For those people who choose not to have surgery, this does not mean going without any treatment at all. There is still a treatment program to be followed emphasizing strengthening the leg muscles and learning to better control the knee and to avoid those situations most likely to cause instability. Many people benefit from this kind of rehabilitation.

- If athletics is a regular part of your life, or if your work is likely to be affected by mild instability of the knee (for example, construction workers or other non-sedentary type jobs), your physician will lean toward reconstructing the torn ligament.

- In general, stronger and fitter is better – and this applies to operated and non-operated knees equally.

Surgery For ACL Tears

Treatment decisions for ACL tears are always individualized – tailored to each individual. The decision whether to offer surgery is based on the person’s age, activity level, how unstable the knee is, and whether other structures in the knee have been injured.

It is important to keep in mind that surgery to reconstruct a torn ACL is not an emergency for most people. Many people with a torn ACL do not need surgery at all. Even though the chances for complete success from surgery are now excellent, surgery is not for everyone. This is because not everyone needs the ligament repaired to return to his or her pre-injury level of function. It is important to distinguish whether the work, recreational, and athletic activities of the person is light, moderate, or strenuous. Another important issue that needs to be understood by the individual considering ACL reconstruction is that it requires many weeks and months of hard work in rehabilitation following the reconstruction. This needs commitment and time.

The Ultimate Deciding Factors…

- Whether the injury is a recent tear or an old ACL problem, individuals need to consider their present activity level and decide if their daily activities and livelihood would be affected by the injury. The question of whether to have surgery to reconstruct the torn ACL arises most frequently with less athletically inclined older persons. Generally in such people, if the instability is severe, and the knee is constantly buckling, the decision to offer surgery is intended to prevent further damage to the knee and stop the daily discomfort of the knee giving way.

- On the other hand, if the knee instability can be controlled by avoiding activities that the individual doesn’t really mind avoiding, then going the “conservative” route and avoiding surgery is often a very good choice – and many people are satisfied with it. Certainly, there are many older athletes who are willing to avoid basketball, soccer, or racquetball, and stick to jogging or biking for fitness. As long as their knees are stable and pain-free for these activities, they are happy. Also with the use of a functional brace, many of these people find they can do most of what they wish to do without significant problems.

- For those people who choose not to have surgery, this does not mean going without any treatment at all. There is still a treatment program to be followed emphasizing strengthening the leg muscles and learning to better control the knee and to avoid those situations most likely to cause instability. Many people benefit from this kind of rehabilitation.

- If athletics is a regular part of your life, or if your work is likely to be affected by mild instability of the knee (for example, construction workers or other non-sedentary type jobs), your physician will lean toward reconstructing the torn ligament.

- In general, stronger and fitter is better – and this applies to operated and non-operated knees equally.

If You Are Going To Have Surgery:

If you are going to have surgery it is important to be both mentally and physically prepared. This includes understanding the injury, the surgery, and the rehabilitation goals.

For most individuals with a torn ACL, reconstruction will restore stability to the knee. Reconstructed knees are reliable and stable. The knee will not give out unexpectedly and will allow the person to return to previous work and athletic activities, usually without any compromises (though it is commonly recommended that a protective brace is worn for athletic activities).

Approximately 90% of individuals return to their previous level of activity without restrictions. For the competitive athlete, this can be extremely important. In some cases, it is even a matter of earning a living or funding a college education. In the case of non-athletes, it can be equally as important in returning to their pre-injury level on and off the job.

Preparing for Surgery

How is the ACL repaired?

Preparing For Surgery

The initial goals before surgery are to:

- Reduce swelling in the knee.

- Try get back the normal range of motion of the knee.

Depending on your age, certain preoperative tests will be arranged, such as blood tests, urine tests, chest x-ray, and an ECG (heart monitoring).

Leg measurements may be taken to order a knee brace. Your rehabilitation program will be discussed in detail with you.

You will meet the anesthesiologist, who may offer you a choice of anesthesia:

- If you choose a general anesthetic, you will be asleep during the procedure.

- If you choose an spinal, an injection is given into the back that numbs the lower half of the body. This wears off a couple of hours after surgery.

If you have an spinal anesthetic, you can often watch the whole operation on the television monitor.

Need to Know:

- If you take aspirin, anti-inflammatory drugs, or blood thinners, you should stop taking them one week before surgery to minimize bleeding. Discuss this with your doctor.

- You should not eat or drink anything (even water) for six hours before surgery. This usually means not eating or drinking anything after midnight the night before surgery.

- If you would normally be taking medication during the hours before surgery, talk to your doctor.

Need to Know:

What to tell your doctor:

Be sure to tell your doctor:

- If you are allergic to iodine or any other drugs

- What medications you take

- About your past medical history

- If you’ve ever had deep vein thrombosis or other blood clotting abnormalities

Also tell your doctor if you develop any of these symptoms prior to surgery:

- Fever or chills

- Irritation of the eyes, ears, throat or gums

- Sniffling or sore throat

- Boils or inflamed skin abrasions and cuts

How Is The ACL Repaired?

There are a number of different techniques available to repair a torn ACL. Each surgeon has his preference for each particular situation.

In fact we don’t talk about ACL “repair” but rather about ACL “reconstruction.” This is because a torn ACL cannot simply be repaired by sewing it together again. This was the method tried in the early days of repairing ACL tears, but it was shown to be ineffective. Thus, newer methods were developed which involve reconstructing the ACL ligament, including substituting a new ligament for the damaged one. Using tendons from other parts of the body as a substitute for the ACL was found to be the most effective way of reconstructing the torn ACL. Currently, the two most popular methods in use are using part of the

Today ACL reconstruction is essentially an arthroscopic procedure, though some surgeons throughout the world still prefer to open the knee.

An

Before actually reconstructing the torn ligament, the surgeon uses the arthroscope to carefully survey the whole joint, looking at and evaluating each key structure. During this portion of the procedure, any additional damage to any of the other knee structures can be identified, and where appropriate, is corrected surgically.

There are a number of choices available to the orthopedic surgeon in determining how best to reconstruct the torn ACL. They all involve a “graft” using something to substitute for the torn ACL.

Each of the available ACL graft tissue choices requires a unique harvesting technique. Furthermore, there are usually different methods used for fixing the grafts in the bone tunnels, depending on the characteristics and properties of the tissue selected. Because of these differences in graft techniques, the type of surgery chosen is frequently made by the surgeon based on his or her experience and comfort level with the chosen technique.

Typically, an ACL reconstruction takes two to two and a half hours. The anesthesia may be general anesthesia or a spinal anesthesia. General anesthesia allows the individual to be asleep through the entire procedure. Spinal anesthesia involves an injection in the back that numbs only the lower body. A medication is also administered with a spinal anesthesia to keep the individual sedated throughout the procedure.

There are several available operative procedures:

1. Patellar tendon graft procedure

Since it was popularized in the mid-1980s, the patellar tendon graft was the the “gold standard” choice for ACL reconstruction. This type of ACL replacement uses the middle third of the person’s own patella tendon and is referred to as a bone-tendon-bone (BTB) graft. However, most surgeons have abandoned this technique in favor of the hamstring graft (see below)

In this particular technique,

- Two tiny incisions for arthroscopic instruments are usually placed on either side of the patellar tendon.

- A one- to two-inch incision is made over the patellar tendon on the front of the knee and the tendon is exposed. The middle one-third of the patellar tendon is carefully removed, together with two bits of bone on either end (hence it is called a ‘bone-tendon-bone graft’).

- Two small tunnels are then drilled into the bones on either side of the joint, in the area where the torn ACL normally attaches to the bone, to allow for fixation of the new ligament.

- The patellar tendon graft is then passed into the joint, placed in a position similar to the original ACL, with the bone pieces at each the end of the graft fitting nicely into the tunnels that have been drilled in the bone.

- The new ACL is then secured with a specialized headless screw in each tunnel.

The patellar tendon graft is tightly secured at the time of the surgery. The knee is stable enough to begin motion and weight-bearing as tolerated, as per the surgeon’s instructions.

As healing occurs, the bone tunnels fill in to further secure the tendon ends of the graft in a bone-to-bone relationship. This occurs over the next six to eight weeks.

Nice to Know:

Recent technology has led to the development of specialized absorbable screws that actually dissolve within the bone over two to three years.

Advantages

- The fixation is very strong

- The patellar tendon replacing the ACL is as strong as the injured ACL (or even stronger).

Disadvantages

- A few people have mild discomfort on the front of the knee, especially when kneeling. This generally settles down within a year. Workers who kneel frequently may need to look at other graft options.

- A normal patellar tendon has been altered. However, this does heal fully again.

Hamstring reconstruction is an alternative to the bone-patellar-bone graft fixation and is growing in popularity. In this procedure, rather than using the patellar tendon, the surgeon uses the patient’s own hamstring tendon, either the semitendinosus or gracilis tendons from the same leg.

There are several variations of this technique. Newer hamstring fixation techniques have been developed to match and even exceed the initial pullout strength of the patellar tendon bone procedure described above. Special screws with threads designed not to cut the hamstring tendons are able to fix the tendon within the bone tunnel, as described with the patellar tendon bone technique.

In younger patients who have torn their ACLs but still have growing bones, the hamstring tendon graft is a good choice because there is less chance of damaging the ‘growth plates’- the area responsible for growth of the bone.

Advantages

- The hamstring incision is away from the patella, allowing patients to kneel comfortably.

- The patellar tendon is left intact.

Disadvantages

- Soft tissue-to-bone healing occurs at a slower rate than bone-to-bone healing.

- Unlike the patellar tendon, the hamstring tendons do not grow back after graft harvest resulting in a slight loss in hamstring strength (approximately. average of 10%) after recovery. However, most people do not notice this slight decline in strength.

Another option is the use of tissue from a cadaver (a deceased person) called an allograft.

Patellar tendon, hamstring tendon, or Achilles tendon allografts can be used as tissues inserted and fixed with the same techniques that are used for autografts (grafts using the individual’s own tissue).

Allografts are a good choice when the patient’s own tissue availability is limited. They are useful for complicated ligament reconstructions needing more than one graft (for example, if both anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments need to be replaced) or if both the ACL and patellar tendon are damaged.

Advantages

- No risks, pain, or scars from the donor site

- Operative time is quicker

Disadvantages

- The very low risk of contracting a serious infection from the cadaver tissue. Newer techniques of tissue radiation have minimized this risk.

- National shortage of allografts due to a high demand combined with a low supply of suitable, qualified cadavers.

Nice to Know:

Synthetic grafts

Synthetic grafts (i.e., grafts made from other materials) were commonly used in the 1970s but were generally unsuccessful.

There are currently no synthetic ligaments in the U.S. approved by the FDA for primary ACL reconstruction.

Researchers continue to try and create the perfect ACL replacement. Major requirements of a prosthetic ligament are that it must be strong, matching the compliance of a normal ACL. It must be durable, withstanding high repetitive loads without wear. It also must be perfectly tolerable to the host without bone, joint, or systemic reaction.

Risks And Possible Complications Of ACL Surgery

Any surgical procedure has possible risks and complications.

The risks and possible complications for ACL surgery include:

- Deep venous thrombosis (DVT)

- Infection

- Stiffness

- Graft ‘impingement’

Surgeons make every effort to minimise these risks.

Deep Venous Thrombosis (DVT)

A thrombosis is a blood clot. Deep venous thrombosis occurs when blood clots form in the blood in the deep veins of the leg. It can occur after any operation, but is more likely to occur following surgery on the hip, pelvis, or knee.

A deep venous thrombosis (DVT) may cause the leg to:

- Swell

- Become warm to the touch

- Become painful

Surgeons take preventing DVT very seriously. Some of the commonly used preventative measures include:

- Encouraging movement of the leg as soon as possible after the surgery. Moving the legs gently reduces the chances of a blood clot forming.

- Pressure stockings worn on the legs that help keep the blood in the legs moving.

- Medications that thin the blood and prevent blood clots from forming.

Infection

The chance of getting an infection following ACL reconstruction is very low. Yet precautions are taken before and after the procedure to prevent this serious complication. Antibiotics are given intravenously just before the start of surgery and again after surgery. Proper care of the surgical incisions by the nursing staff, and thorough education about proper incision care prior to discharge from the surgical center, will limit the chance of infection. The meticulous work of the surgeon is another important factor in preventing infection.

Stiffness

Although rare, excessive scarring inside the knee joint after ACL reconstruction can lead to an increasingly stiff knee. Range-of-motion exercises immediately after surgery are important to prevent knee stiffness. Physical therapy is begun shortly after the surgery. Stiffness can occur if the surgery was performed too soon after the injury, when the knee was not yet able to bend through its normal range of motion. That’s why a surgeon will not reconstruct a torn ACL unless the knee is moving well.

Graft Impingement

If the drill holes in the bone (the bone tunnels that were made to hold the new ACL) are incorrectly placed, then the newly placed graft may press against the bone as the knee bends or straightens, and restrict the normal movement of the knee. Most commonly, it becomes impossible to fully straighten the knee.

Occasionally this problem may resolve with physical therapy. Usually, another arthroscopic procedure is required to shave away some of the obstructing bone to give more room for the new graft. This may not resolve the problem and further surgery may be required to drill new tunnels in order to place the graft in the proper position inside the knee.

Risks And Possible Complications Of ACL Surgery

Any surgical procedure has possible risks and complications.

The risks and possible complications for ACL surgery include:

Surgeons make every effort to minimise these risks.

Deep Venous Thrombosis (DVT)

A thrombosis is a blood clot. Deep venous thrombosis occurs when blood clots form in the blood in the deep veins of the leg. It can occur after any operation, but is more likely to occur following surgery on the hip, pelvis, or knee.

A deep venous thrombosis (DVT) may cause the leg to:

- Swell

- Become warm to the touch

- Become painful

Surgeons take preventing DVT very seriously. Some of the commonly used preventative measures include:

- Encouraging movement of the leg as soon as possible after the surgery. Moving the legs gently reduces the chances of a blood clot forming.

- Pressure stockings worn on the legs that help keep the blood in the legs moving.

- Medications that thin the blood and prevent blood clots from forming.

Infection

The chance of getting an infection following ACL reconstruction is very low. Yet precautions are taken before and after the procedure to prevent this serious complication. Antibiotics are given intravenously just before the start of surgery and again after surgery. Proper care of the surgical incisions by the nursing staff, and thorough education about proper incision care prior to discharge from the surgical center, will limit the chance of infection. The meticulous work of the surgeon is another important factor in preventing infection.

Stiffness

Although rare, excessive scarring inside the knee joint after ACL reconstruction can lead to an increasingly stiff knee. Range-of-motion exercises immediately after surgery are important to prevent knee stiffness. Physical therapy is begun shortly after the surgery. Stiffness can occur if the surgery was performed too soon after the injury, when the knee was not yet able to bend through its normal range of motion. That’s why a surgeon will not reconstruct a torn ACL unless the knee is moving well.

Graft Impingement

If the drill holes in the bone (the bone tunnels that were made to hold the new ACL) are incorrectly placed, then the newly placed graft may press against the bone as the knee bends or straightens, and restrict the normal movement of the knee. Most commonly, it becomes impossible to fully straighten the knee.

Occasionally this problem may resolve with physical therapy. Usually, another arthroscopic procedure is required to shave away some of the obstructing bone to give more room for the new graft. This may not resolve the problem and further surgery may be required to drill new tunnels in order to place the graft in the proper position inside the knee.

Recovery After ACL Reconstruction

Patients generally stay in the recovery room following surgery. Depending on the type of anesthetic that was used, it takes about one to two hours to recover enough to be able to sit up, eat some light food, use the bathroom (with crutches), and feel ready to go home.

Some surgeons prefer their patients remain in the hospital overnight. Other surgeons are happy for their patients to return home four to six hours after surgery. The nursing staff will educate patients about home medications and will give instructions about when to change the surgical dressing.

The physical therapist becomes an important part of the rehabilitation program. Rehabilitation begins immediately after surgery, which involves walking with crutches, contracting the thigh muscles, and attempting to lift the leg independently.

By working with the physical therapist, most patients are able to walk quite easily with crutches by one week after surgery. They are also able to lift their leg without assistance from a position lying on their back, and by the end of the second week after surgery can walk without crutches. The length a patient needs to wear a knee immobilizer following surgery will depend on the surgery and the preference of the surgeon.

Going Home

Even though many ACL surgeries are now done as outpatient procedures, the individual will not be able to drive home from the surgical center.

- Prior to leaving, education will be given by the nursing staff regarding pain control as well as care of the incisions.

- Crutch training (how to use crutches) will be done at that time or may have already been done before the surgery.

- Depending on the preference of the surgeon, weight bearing will usually be allowed.

- Crutches are usually needed for at least a week or two, with gradual progression to one crutch and finally to independent walking.

- Also depending on the surgeon’s preference, a brace may or may not be used. Some surgeons prescribe a rehabilitation brace that is adjustable and can be locked in a straight position or set to allow a certain amount of movement. Sometimes, a brace that prevents all bending movements may be used. However in either case, the brace will normally be taken off for certain exercises.

Keeping Comfortable

Once at home, the treatment of RICE as discussed earlier, three to five times a day for 20 minutes each time, is recommended.

- Rest – Getting off the leg periodically throughout the day and resting the knee on pillows is recommended, to avoid excess postoperative swelling and pain.

- Ice – Placing a cold compress or ice pack around the knee controls pain and swelling.

- Compression – Carefully placing an ace wrap for compression around the knee is beneficial to control the swelling. Be careful that the wrap is not too tight to interfere with circulation to the lower leg.

- Elevation – Lying down with the knee in a cold compress and elevated higher than the level of the chest is helpful in controlling and reducing swelling.

Need To Know:

Precautions Following Surgery

- Keep the incisions dry for the first seven to 10 days.

- Some fluid on the knee is normal following the reconstruction. However, the physician needs to be contacted if any of the following are present:

- Increased redness

- Increased swelling

- Bleeding in the joint or from the arthroscopic incisions

- Increased pain

- Depending on the preference of the surgeon, the amount of weight placed on the operated leg after surgery will vary, as will the decision of whether or not to brace the knee.

- Some surgeons prefer to have the brace locked straight while walking for the first few weeks, but allow the brace to bend from being straight to 90 degrees. Other surgeons encourage bending of the knee immediately. As the patient progresses with strength, range of motion, and confidence, the brace may be allowed to bend during walking.

Early Post-Surgical Exercises

The following exercises are recommended early in the rehabilitation phase even before any significant amount of weight is placed on the leg.

With each foot separately or at the same time, point and flex the toes as if pumping the gas pedal of a car repeatedly, 25-50 times every five to 10 minutes.

With each ankle separately or at the same time, rotate the ankles in a large circle about 10 times each direction, 25-50 times every five to 10 minutes.

This exercise will promote muscle activity of the hamstrings as well as help increase the amount of knee flexion.

- Lie on the bed on your back, with legs straight and together and arms at the side.

- Bring the heel of the operated leg toward your buttock to a point where a mild stretch is felt.

- This position is held to a count of ten. Slowly return to the starting position.

- This is repeated five to 10 times, two-three sets (one set described as when the exercise has been performed five-10 times) twice daily.

This is a good beginning exercise, as it not only initiates the needed muscle contraction, but is also helpful in increasing extension of the knee.

- Lie on the bed on your back, with legs straight and together and arms at the side.

- Push the back of the knee downward onto a flat surface.

- Hold for five to 10 seconds, followed by relaxing for a short period of time.

- Repeat five to 10 times, two-three sets (one set described as when the exercise has been performed five-10 times) twice daily. (The amount of discomfort will determine how many each individual can perform.)

This is another excellent exercise to promote strength to the quadriceps and the flexor muscles important in walking.

- Keeping the operated leg as straight as tolerated, raise it approximately six to ten inches upward.

- Hold for five-10 seconds, and then lower slowly to the start position.

- Repeat five to 10 times progressing to 20 times, two-three sets twice daily (one set described as when the exercise has been performed five-10 times).

Once this exercise can be done without any difficulty, gradual resistance at the ankle (such as the use of ankle weights) can be used to further strengthen the muscles. The amount of weight used should be increased in no more than one-pound increments. The individual bends the uninvolved leg by raising the knee and keeping the foot flat on a flat surface. This will help decrease or avoid unwanted strain on the lower back region.

Outpatient and Physical Therapy for ACL Tears

About a week after the surgery, the physician will inspect the knee and discuss a rehab program. This will be done on an outpatient basis and may begin one to two weeks after surgery.

The rehabilitation program following ACL reconstruction is very important and has a significant impact on the outcome of the knee.

Many therapy programs follow specific guidelines and protocols developed by the physician. The following is one example of a rehabilitation program. However, programs may vary and need to be followed per physician protocol.

- Phase One (first couple of weeks after surgery)

- Phase Two (weeks three and four)

- Phase Three (week four to six)

- Phase Four (week six to eight)

- Phase Five (week eight to 10)

- Final Phase: (return to activity)

ACL Post-Surgical Program

1. Phase One (first couple of weeks after surgery)

This period of the rehabilitation is called the early rehabilitative phase. This phase focuses on decreasing the pain and swelling following surgery.

Many of the exercises described earlier are included in this phase as they aim to:

- Improve range of motion

- Promote muscle activity and strength

If the individual is using any form of cane/crutch for walking, this is generally discontinued at this point unless otherwise required by the surgeon.

2. Phase Two (weeks three and four)

In the second rehabilitation phase (three to four weeks after surgery), more attention is placed on joint protection as the pain has mostly disappeared and the individual may want to try more things that the knee is not ready to perform.

Key areas and examples of exercises of this phase are:

- Being able to bend the knee zero to 100 degrees.

- Water exercises may be recommended either at the clinic or within the home program, such as knee bending/straightening and pool walking with emphasis on forward, backward, and sideways movement.

- Mini wall-squats may be performed, beginning by standing with the back to the wall, then lowering the body by bending at the knees to approximately 45 degrees and returning to an upright position. Progressing from standing on both legs to standing on the surgical leg only can advance this exercise

- Stair-master machines in a sitting position are beneficial, as is the use of a stationary bicycle.

- Emphasis on balance activities is addressed at this point. Further strengthening with step-ups is useful (forward, backward, and side-to-side using a step with a height of two, four, and six inches respectively).

- Leg-press machines are used within a pain-free range of motion.

- Progress using a stair-stepper from a sitting position to a standing position at three-four weeks if good quadriceps control is present.

3. Phase Three (week four to six)

Referred to as the controlled ambulation phase, week four to six includes all the former exercises plus a few more.

Key areas and examples of exercises of this phase are:

- Aim to bend the knee from zero to 130 degrees

- Single leg mini squats

- Single leg bridges

- Step up/step downs with a four-eight inch step

- Calf strengthening and stretching

- Increased resistance on the stationary exercise bike

This is an important time for exercises requiring improved balance both in the clinic as well as the home program:

- While standing on a pillow or a roll of foam 6 inches thick, reach forward as far as possible with hands clasped together at 12, three, six and nine o’clock patterns without losing balance.

- Gait training on the treadmill, using a slight incline and progressing to pedaling backwards.

4. Phase Four (week six to eight)

Week 6 to 8 is referred to as the moderate protection phase.

Key areas and examples of exercises of this phase are:

- Full range of motion of the knee

- Weights may be added to gradually increase resistance to existing exercises

5. Phase Five (week eight to 10)

This light activity phase at eight to 10 weeks after surgery places additional emphasis on strengthening exercises with increased concentration on balance and mobility.

Key areas and examples of exercises of this phase are:

- Lunges, which are appropriate if the knee can bend in a pain-free manner to 90 degrees.

- Repeatedly stepping up and down a height of four to eight inches, which is useful for developing quadriceps control.

- Stepping exercises using the resistance of a sport cord, which can be the next progression of this exercise in this period.

6. Final Phase: Return to Activity

The final phase starts at about 10 weeks and continues until the desired activity level is reached. Key areas and examples of exercises of this phase are:

- If necessary, fitting of a functional brace for athletic activities and /or work situations.

- Jogging on treadmill with no sudden starts and stops can be started at this point, as well as moderate intensity agility drills using box jumps while wearing the functional brace.

- Many surgeons will request

isokinetic testing (a type of exercise where resistance is at a constant preset speed) at three and six months, with the addition of functional tests such as the timed hop, hop for distance, and cross-over hop.

Returning To Work And Activities After ACL Surgery

These are the general guidelines for returning to work and returning to sports following ACL surgery. There is great variation in the time span needed for each individual.

Returning To Work

Returning to work will depend on the physical nature of the activity:

- If your job involves sitting down, some surgeons may allow return to work as soon as a week after surgery.

- If your job requires standing, it may be four to six weeks before return to work is recommended.

- If your job requires lifting moderate loads or climbing activities, recovery time may need to be as long as two to four months.

Return To Sports

Expect to be able to…

- Jog at four months

- Road cycle at four to five months

- Run in a straight line at five months

- Perform agility drills such as figure eight’s, as well as light cutting using the functional brace, at around six to eight months

To achieve this successfully, you need to stick with the rehab program arranged by your surgeon and physical therapist.

To achieve this successfully, you need to stick with the rehab program arranged by your surgeon and physical therapist.

Sports-specific changes may be initiated anywhere from four to 24 months, depending upon the physician’s protocol.

Nice To Know:

A rule of thumb in returning to sports activities following ACL surgery is that the injured leg should have 85 to 90 percent of the quadriceps and hamstring strength compared to the pre-surgical level.

This is determined by the physical therapist or physician using simple strength tests called

Q: What kind of brace will I be using when I return to my sport after rehabilitation?

A: There are several types of braces on the market that protect the knee joint. They are all relatively light and user friendly. One important aspect some ACL braces have is that in order to unload stress on the ACL graft, the sequence of fastening the straps of the brace (usually four or five) is very important.

Q: I like to snow and water ski. Can I still do these activities after ACL reconstruction?

A: Unless the surgeon advises otherwise, most people return to enjoying both of these sports with the use of a brace. However, remember every individual injury is different. Following the recommendations of the surgeon is of utmost importance.

What Can I Expect After My ACL Reconstruction?

For most individuals with a torn ACL, reconstruction will restore stability to the knee. Reconstructed knees are reliable and stable. The knee will not give out unexpectedly and will allow the person to return to previous work and athletic activities, usually without any compromises.

A protective brace is often recommended for athletic activities.

Approximately 90% of individuals return to their previous level of activity without restrictions. For the competitive athlete, this can be extremely important. In some cases, it is even a matter of earning a living or funding a college education. In the case of non-athletes, it can be equally as important in returning to their pre-injury level on and off the job.

Nice To Know:

Q: What kind of brace will I be using when I return to my sport after rehabilitation?

A: There are several types of braces on the market that protect the knee joint. They are all relatively light and user friendly. One important aspect some ACL braces have is that in order to unload stress on the ACL graft, the sequence of fastening the straps of the brace (usually four or five) is very important.

Q: I like to snow and water ski. Can I still do these activities after ACL reconstruction?

A: Unless the surgeon advises otherwise, most people return to enjoying both of these sports with the use of a brace. However, remember every individual injury is different. Following the recommendations of the surgeon is of utmost importance.

Frequently asked questions: ACL

What you need to know about the ACL:

- The ACL is short for the Anterior Cruciate Ligament

- The ACL is one of the 2 strong ligaments inside the knee joint. The other is the PCL (posterior cruciate ligament).

- Cruciate means ‘crossing’. The 2 ligaments inside the knee ‘cross’ each other.

- The primary function of the ACL is to control forward movement of the tibia on the femur as well as to restrain excessive inward rotation of the tibia in relation to the femur.

- Injuries to the ACL occurs more commonly in athletes but occur commonly in non-athletes as well.

- Injuries to the ACL occur most often in contact sports or activities requiring sudden stops and turns.

- Not all ACL injuries need surgery.

- The decision as to whether to have surgery will depend on how active the person is.

- A torn ACL cannot simply be repaired. The torn ends cannot just be brought together and fixed. It will not heal or hold.

- Surgery for a torn ACL is therefore called a ‘Reconstruction”. The ACL is replaced by a tendon that takes the place of the ACL.

- Two common tendons used in the reconstruction of the ACL are the patellar tendon and the hamstring tendon.

- ACL reconstruction can now be performed on an outpatient basis using keyhole surgery (arthoscopically).

- The rehabilitation program following ACL reconstruction is very important and has a significant impact on the outcome of the surgery.

- Most therapy programs follow specific guidelines and protocols.

- For most individuals, ACL reconstruction can restore stability to the knee and will allow them return to previous work and vigorous athletic activities usually without any compromises.

Here are some frequently asked questions related to anterior cruciate ligament tears.

Q: I have been recently diagnosed with an ACL tear and my physician wants to do an MRI to confirm his diagnosis. Wouldn’t a plain x-ray be much less expensive and less time-consuming?

A: Plain x-ray films will only show bone tissue rather than soft tissue structure. Since the ligament is soft tissue in nature it will not show on an x-ray.

Q: How much physical therapy will I need after the ACL reconstruction?

A: One of the main priorities after ACL reconstruction is to regain the knee range of motion. This, along with establishing a good strengthening program, is usually best done two-three times per week for the first four-six weeks. Because many insurance policies will not cover this many visits to the therapist, an independent home program may need to be instructed earlier. It is important to comply with any exercise program at home and in a clinical setting.

Q: My friend had her ACL reconstructed and was allowed to discontinue the brace after two weeks. I have been instructed to keep wearing my brace for four weeks after surgery. Why the difference in recommendations?

A: Every surgeon has different experiences and philosophies. Also, each particular injury is different and surgeries are different. The important thing is to adhere to the surgeon’s recommendation for optimal results.

Q: What kind of brace will I be using when I return to my sport after rehabilitation?

A: There are several types of braces on the market that protect the knee joint. They are all relatively light and user-friendly. One important aspect some ACL braces have is that in order to unload stress on the ACL graft, the sequence of fastening the straps of the brace (usually four or five) is very important.

Q: I like to snow and water ski. Can I still do these activities after ACL reconstruction?

A: Unless the surgeon advises otherwise, most people return to enjoying both of these sports with the use of a brace. However, remember every individual injury is different. Following the recommendations of the surgeon is of utmost importance.

Glossary For Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears

Here are definitions of medical terms related to anterior cruciate ligament tears.

Allograft: Tissue obtained from a donor to be used in another person.

Autograft: Tissue taken from one place in the body to be used in another place in the same body.

Arthroscope: A narrow telescope-like instrument to which a tiny camera is attached. It is inserted into the joint through small incisions, allowing the inside of the joint to be clearly seen.

Cartilage: The smooth tissue that lines the bone ends inside a joint.

EKG: an electrocardiogram, a simple test that measures the electrical impulses produced by the heart.

Femur: The upper leg bone. It is the largest and strongest bone. It is also referred to as the thighbone.

Isokinetic: this refers to a muscle contraction in which the maximum tension is generated in the muscle as it contracts at a constant speed over the full range of motion of the joint.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): painless method of diagnosis using powerful magnets and computers to give detailed images of the inside of the body.

Meniscus: A soft padding that acts as a cushion or “shock absorber” between the ends of bones in some joints.

Patella: The kneecap. A flat triangular bone located at the front of the knee joint.

Tibia: The larger of the two bones of the lower (between the knee and ankle). Also referred to as the shin bone.

Retinaculum: A band or band like structure aiding in holding an organ or other structure in place.

Additional Sources Of Information On Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears

Here are some reliable sources that can provide more information on anterior cruciate ligament tears.

American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons

Phone: 847/823-7186

Phone: 800/346-2267

World Wide Web address: http://www.aaos.org

American Physical Therapy Association

Phone: 800/999-APTA (2782)

World Wide Web address: http://www.apta.org

Articles Found Useful for ACL Tears

Bernard R. Bach, Jr. MD. Acute Knee Injuries: When to Refer. The Physician and Sports Medicine. Volt 25 – No. 5 – May 1997

Discusses mechanisms of injury, diagnosis, and treatment of the knee with emphasis on determining when an orthopedic specialist should see the knee injury. Discusses several types of knee injuries including ligament injuries and

Article usefulness: 5

James L. Moeller, MD; Mary M. Lamb, MD. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Female Athletes: Why Are Women More Susceptible? The Physician and Sports Medicine. Volt 25 – No. 4 – April 1997

This article covers the structural and biomechanical factors that may predispose females to injury of the anterior cruciate ligament. Discusses structural differences between males and females placing increased stress and loading on the knee joint during specific athletic activities.

Article usefulness: 5

Todd Arnold, MD; K. Donald Shelbourne, MD. A Preoperative Rehabilitation Program for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Surgery. The Physician and Sports Medicine – Vol. 28 – No. 1 – January 2000

Discusses and educates about the proper steps following an ACL injury to reduce inflammation and pain. Describes the sequence of rehabilitation as well as describes a program to help the individual prepare for reconstructive surgery.

Article usefulness: 5